My Gutenberg in Tears

The Substance of Publishing: A Reflection on Academic DesignRead this article and more on Substack

2025

Essay

Verily, many will instantly evoke the concepts of functionality, productivity, efficiency and, of course, capitalism as culpable parties involved in the crime I am describing. They are easy to name. However, we can not blame everything on these human concepts while removing any type of responsibility from the humans themselves. Nietzsche said "God is dead", then Hawking announced the passing of philosophy, likewise we have declared “deaths” of art, cinema and print… a particular trend, isn’t it? Death is so beautiful and certain, helps us cut difficult changes into understandable bites, right? Well, we can say with certainty - curiosity has been buried too. The only problem is - unlike the aforementioned concepts, curiosity is not an external force, but an innate part of the human psyche, the one we shouldn’t be willing to let go of. I will return to this thought at the end, first we shall disassemble this chaotic result of my pensive evening.

Academic publishing today

The question of whether to publish in print may seem, at first, an anachronistic one. In a digital era where information is abundant and constantly shifting, the permanence of the printed book might appear unnecessary, fleeting, even cumbersome. But publishing in print — whether in journals or books — must remain a foundational practice of scholarship, not simply as a means of dissemination, but as a structuring force in how knowledge is preserved and engaged with over time. Equally, I believe, we shouldn't dismiss its role as a ritual and tradition connecting our thoughts through the matter of time and, yes, space.Today’s publishing is very much a single-faceted ordeal. Most academic works find themselves in online journals, platforms such as Jstor or Academia (for example) and very rarely do they acquire a tangible body for themselves. This shift toward digital publishing is naturally justified by accessibility, speed, and sheer quantities of information that are being produced. In certain areas of knowledge, particularly the ‘hard’ sciences, research advances incrementally, requiring rapid dissemination, which the aforementioned online repositories provide immediate access to. In turn, facilitating simultaneous advancements internationally. Hence, yes, the value of online publishing in the global and rapidly advancing research community is undeniable. And my argument here doesn’t intend to go against it.

However.

There is surely a ‘but’. And this emphasis on efficiency has had unintended consequences. Which ones, might you ask? Well, what happens when any given work gets printed today? Either it takes the form of a near-DIY birth through the university printer with minimal functional design qualities; or if the subject of the work is quasi-popular (or written in a simpler style) bringing it closer to profitability - then bigger publishers take over and design regains its importance. Even so, the latter (the lucky ones) are usually reduced to a very strict subject list, mostly related to art, history or social sciences.1 A pity, I’d say in the least.

1. It is important to acknowledge a much more developed practice of research

publishing in some Northern European countries, such as Netherlands or Germany,

which, nonetheless is also limited to cultural and social sciences studies.

publishing in some Northern European countries, such as Netherlands or Germany,

which, nonetheless is also limited to cultural and social sciences studies.

The visual and material qualities of academic work—once seen as integral to knowledge transmission — have been sidelined today, with numerous elements having contributed to this neglect. In the pursuit of perceived objectivity and quantifiability, aesthetics have been dismissed as irrelevant distractions, making it almost ‘frivolous’ to present your work in less than a Word Document export to a PDF file. Yet, the absence of visual consideration does not make research more rigorous; in fact, it merely renders it less loved.

Without a doubt, there are several opposing arguments in this discussion. For the sake of narrative cohesion, I will focus on the empirical ones, which will lead me back to curiosity, I promise.

- To begin with, in academia - visibility is currency. We agree on that. And of course, we can not be promoting and printing with utmost care every single thesis written by every single Master or PhD student there is. We’ve all been there - the majority of such work is written as a means to an end or sometimes, rather trivially, the subject of the paper carries very little new knowledge. However, this shouldn’t be discouraging to everyone. Making it about selection - not as an obstacle, but as a step. Perhaps… university presses should indulge us… more..?

- Furthermore, a researcher’s work is often measured by where and how frequently it is cited, a system that can feel mechanistic in its reliance on impact factors and citation indexes. But to reduce publishing to a game of metrics is to overlook its actual value. In the classical sense, knowledge is not only for storage but for engagement. In Arendt’s words: “thought itself arises out of incidents of living experience,” (just as this text is emerging out of experiences of my own) and academic publishing, at its best, is a way of extending thought beyond the confines of an institution, ensuring it interacts with and shapes the world beyond its origins. How much of a living experience does reading an AI-generated summary of a digital journal article provide, in your opinion?

Thus we have — selection & engagement. Two essential elements to which it all boils down. Two elements that bring us to curiosity. Two elements that suffer at the lack of it. How can the selection of academic work for publishing function when the public it is supposed to be educating isn’t curious about the world around them? How can we engage with the knowledge that is produced, with the medium that carries it, when we have little curiosity for the tangible living experiences? When there is no passion in learning?

A thoughtfully curated, well-designed publication signals that the work it contains has been considered, refined, and presented with care - embodying ‘selection & engagement’ concepts. Thoughtful typography, layout, and material quality can make complex ideas more inviting, particularly for those unfamiliar with a subject. And the whole beauty of learning is in interaction with those who are unfamiliar. A carefully designed journal can draw in non-experts, students, or even casual readers—because, to put it simply (and justly) in the words of my dear friend, "pretty pages make everything cool."

The Age of Quick Experiences

We still remember, from a couple of paragraphs above, the mention of consequences toiling the chase for efficiency in academia. But the most damning of them all is the consequence our mind suffers: the erosion of natural curiosity. Once attributed primarily to conformity-driven education systems (see Engel, The Hungry Mind), this decline is now increasingly tied to the digitalisation of information, the infinite scroll of media, and a near-addictive dependence on speed, productivity, and efficiency (same triggers that we have seen outlined in the context of academic research, aren’t they?). Rather than fostering deep engagement, these mechanisms encourage shallow consumption, where the rapid intake of fragmented and visually repetitive content replaces sustained intellectual exploration. Attention, a scarce and valuable resource, has been fragmented into moments of fleeting stimulation, making the pursuit of knowledge feel more like a task to be optimised rather than an experience to be savoured (more in Crawford, The World Beyond Your Head). This is how we now find ourselves in the world where knowledge is consumed but not comprehended, skimmed rather than truly absorbed.What's worse, in my bitter opinion, is that little to none steps are made to confront these tendencies, instead we only seem to continue facilitating the slow suffocation of our intellectual agility, more and more and more… “Tired of reading all your research papers?” - says one advertisement on Instagram - “This AI tool will summarise all the texts you put in and provide you with key notions around its subject” it continues. And none of these tools ever mention that they serve to support, not to replace proper learning. None of these ‘optimisations’ seem to be aware of themselves walking backwards.

Now, this is a subject that deserves volumes of its own, but how does this finally link to the design and print of academic research? I see the impatience in your eyes, my dear reader. And I oblige.

A well-designed publication does more than house knowledge; it communicates its significance. This value is reflected in both the diversity of subjects covered and the visual language used to present them. Thoughtfully designed research stands out — not merely as text, but as an experience that invites deeper engagement. And print, as a slow and deliberate medium, plays a crucial role in this process. Unlike the fleeting nature of digital content often presented in the same ‘efficient’ layout, printed works allow for immersive interaction, where thoughtfully crafted visuals and material presence reignite curiosity. A beautifully designed journal or book does more than inform — it intrigues, captivates, and transforms passive reading into active intellectual pursuit. An adventure, if you will.

Once more, there is no argument against the utility of online publishing. But to stimulate deeper engagement with ideas, printed matter remains essential. To write a book is to commit to a mode of thinking that unfolds over time rather than being compressed into few pages of argumentation — allowing for complexity, depth, and a lingering intellectual presence, an environment that nurtures curiosity rather than catering to passive consumption.

And no, this is not nostalgia; it is an acknowledgment of form. Books offer a different kind of intellectual presence — one that persists. In that sense, book publishing is never a return to the past but a recognition that certain formats still serve scholarly pursuits in ways that digital acceleration cannot replace. And I know some feel visceral pain at the idea of something from ‘the past’ still being relevant today. But we will all learn to live with it.

Having been kindled, curiosity thrives in spaces where knowledge is pursued for its own sake. The passion for scavenging through library shelves, flipping through indexes of books, running your finger down the page in search of that special passage that will either ruin or confirm your theory — this is the essence of intellectual discovery. There is an almost adrenaline-like sensation ignited by the pursuit of understanding, by the slow and deliberate engagement with a subject, by the romance with it. This is what print — what books — still offer in an age of instant information.

The Design of Ideas

Yet the question remains: how should research be presented? The passionate experiences I describe above stem from a natural thirst for knowledge, yes, but also from the way information is encountered. We are visual and sensual beings, shaped by how we interact with the material world, and we must reintroduce an element of craftsmanship into knowledge production.Typography, layout, paper quality, and binding are not frivolous concerns. They are integral to how research is perceived, engaged with, and remembered. The history of bookmaking, from medieval manuscripts to Renaissance folios to the Bauhaus movement’s experiments with typography, illustrates that design has always mattered in the transmission of knowledge. Design should echo the subject, something that Times New Roman in 12pt with 1,5 leading simply won’t do.

A book, after all, is a conversation between author and reader, where design facilitates that dialogue.

This is also what allows us to expand our appreciation criteria to a smaller medium such as printed scientific journals, through which design can also serve an institutional purpose. A well-branded, visually distinct academic journal does not merely collect research — it establishes itself as a recognisable entity, lending credibility and identity to the work it publishes. Just as renowned journals and publishers are known for their editorial quality, they also should be recognised for their design sensibilities, which at the moment seems to be a lost cause (I’m sorry Lancet, this is not personal). This benefits not only the publishers but also the researchers themselves, as their work gains visibility and authority through association with a publication that is as well-crafted as it is well-curated, hence likewise increasing its chances to intrigue a non-expert that comes across it one day.

In an age of rapid information exchange, taking the time to publish thoughtfully—to craft a book that is both rigorous and beautifully designed — is a deliberate act of resistance against the fleeting nature of digital consumption. It is a commitment to enduring scholarship, to ideas that deserve more than a momentary glance. For students, early-career researchers, and established academics alike, the decision to publish a book is a statement about the value of their work beyond the immediacy of academic cycles. For those who see the value in thoughtful publishing, the question is not whether to print — but how to do so with purpose.

Where does it leave us now?

If curiosity has been buried, then it is our duty to unearth it. To publish with intention is not just an act of intellectual engagement but of defiance — against disposability, against the erosion of depth, against the loss of craftsmanship in scholarship. The question is not whether print should have a bigger role in academia, but whether we are willing to cultivate the curiosity required to give it meaning. This is not about making scientific works accessible to children, flooding them with colourful illustrations and bright neon schematics and this is not merely a call to nostalgia but a challenge to rethink our intellectual and physical practices. If knowledge is to remain a living force, we must reclaim the patience, care, and materiality of publishing as a process that fosters that force. Scholarship should not be reduced to fleeting bytes of information; it should persist, evolve, and challenge us — just as curiosity always has.Perhaps, just perhaps, sometimes we can write notes on paper, get inspired by looking at the binding of an old book, find thoughts in the flipping of encyclopaedia pages and the smell of dust surrounding us. Perhaps, just sometimes the “ah, wait!” can come out of nothing, after a long empty glance at the bookmark in front of us.

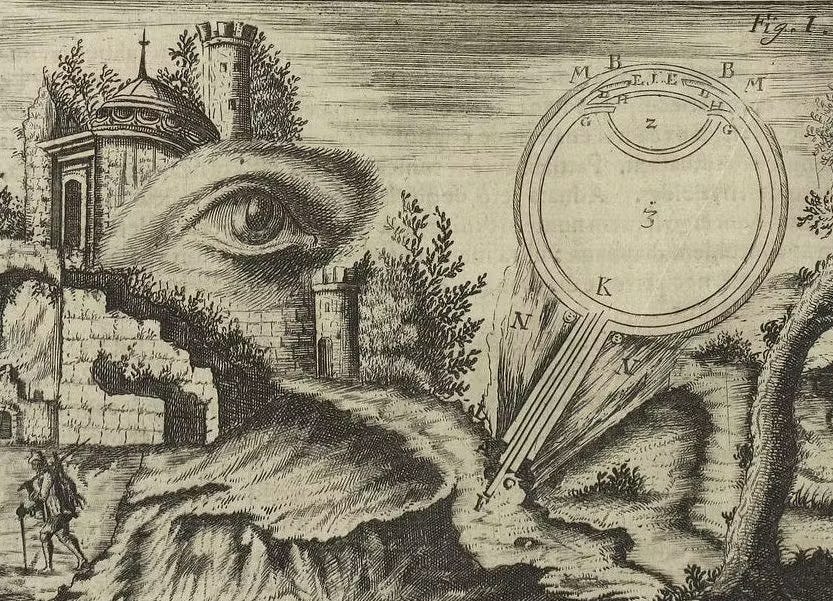

Image to the left: Images from Johann Zahn’s Oculus Artificialis (1685)